Nokia N810: Close, but no

maemo.org packages listing works, but the subdomain that hosts the .deb files doesn’t. Wayback Machine to the rescue! What a blessing Archive.org is.

You can use these URLs to browse the package listings:

- https://web.archive.org/web/20250210062931/http://repository.maemo.org/extras/pool/diablo/free/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20250210062931/http://repository.maemo.org/extras-devel/pool/diablo/free/

Replace diablo with chinook if you need packages from that OS. I download them on my desktop computer, copy the .deb file to my N810 and then either use dpkg -i package-name.deb or use the Package Manager application. I prefer the dpkg way because it lists missing dependencies, if any.

I installed and got working:

- MilkyTracker, but the interface is oh so small and impractical. I thought I had found the «killer app» for my N810 but it’s way too cumbersome, boohoo.

- CBRPager, a comic reader. The screen is too small to be readable. I don’t have good eyes anymore.

- vncviewer, for some reason, the remote screen is turned sideways. That’s no problem. What is a problem is not having Function keys and, especially, the Meta key I require to operate on my remote desktop. Bummer.

I tried a lot more programs, they get pretty close, but «no.»

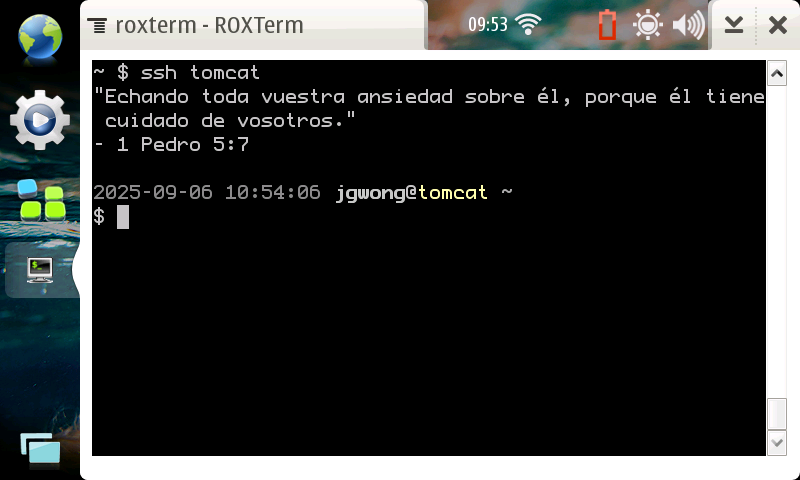

I created a simple web page, served from Tomcat with PHP, plain old unencrypted HTTP. It works. I’m discovering what this small web browser can do. It’s a stripped-down version of Mozilla called MicroB and I find very hard to remember what it can do in terms of CSS and JavaScript.

This would be much more versatile than using a terminal emulator with tmux but there’s something about leaving the screen always on when charging that bothers me. But, on the other hand, it wouldn’t be useful if I had to be unblanking the screen manually.

This is turning again into another «close, but no.»

Another idea would be to copy the HTML file into the N810 and load it locally. Upside is, if network goes down, it will still work. Downside is, I can’t do server-side dynamic stuff with PHP or something. And copying assets (images) would be slower.

Yes, there’s PHP Maemo packages. They’re version 5.3. But the built-in web server was released in 5.4. Close, but no.

Yeah, let’s just treat it like a thin, dumb terminal.

I tried pairing my Apple Wireless Keyboard via Bluetooth. It worked! But there’s a noticeable lag, it’s not instantaneous. Yes, «close, but no» again. It’s usable, tho, not the end of the world, if you see it from the angle of «it’s an slightly faster keyboard than the built-in keyboard,» but I’m not keen on carrying two devices as of now.

So, to recap:

- It works for SSH work sessions with tmux; there’s glitches, but it’s usable.

- I can build simple web pages for it. Lots of possibilities here. It does a great job given its vintage.

- eBook reader, or short articles reading. Also does a good job here.

You know what’s cool? I copied over the JetBrains Mono Nerd Font and it worked! I’ve got Nerd Fonts in my N810 terminal emulator! Take that, Termius!

I don’t like the idea of using it as a «monitor» or secondary screen. I don’t think that screen’s designed to be always-on.